© Copyright 2005 by AELE, Inc.

Contents (or partial contents) may be downloaded,

stored, printed or copied by, or shared with, employees

of

the same firm or government

entity that subscribes to

this library, but may not be sent to, or shared with others.

A Civil Liability Law Publication

for Law Enforcement

ISSN 0271-5481

Cite this issue as:

2005 LR Feb (web edit.)

Click here to view information on the editor of this publication.

Return to the monthly publications menu

Access the multi-year Civil Liability Case Digest

Report non-working links here

Some links are to PDF files

Adobe Reader™

must be used to view content

Defenses: Qualified

Immunity

Domestic Violence

False Arrest/Imprisonment: No

Warrant (2 cases)

False Arrest/Imprisonment: Unlawful

Detention

Firearms Related: Intentional

Use

First Amendment

Other Misconduct: Eviction

Property

Pursuits: Law Enforcement

Search and Seizure: Home/Business

(2 cases)

Administrative Liability: Training

Assault and Battery: Handcuffs

Assault and Battery: Physical

Defenses: Collateral Estoppel

Defenses: Sovereign Immunity

Defenses: Qualified Immunity

Dogs

False Arrest/Imprisonment: No Warrant (5 cases)

False Arrest/Imprisonment: Warrant (2 cases)

Firearms Related: Intentional Use (2 cases)

First Amendment (3 cases)

Governmental Liability: Policy/Custom

Malicious Prosecution

Off-Duty/Color of Law: Vehicle Related

Police Plaintiffs: Firefighters' Rule

Search and Seizure: Home/Business

Search and Seizure: Vehicle

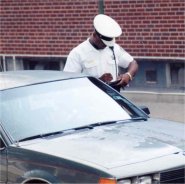

Issuing summonses to appear in court to a motorist who refused to provide information at the scene of an accident concerning his auto insurance status did not violate his Fourth or Fifth Amendment rights, and individual defendants in his federal civil rights lawsuit were entitled to qualified immunity.

A Virginia motorist claimed that it violated his Fourth Amendment right against unlawful seizure and his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination for city officials to summon him to appear in court after he refused to provide evidence of auto insurance at the scene of an accident.

A federal appeals court upheld summary judgment for the defendants, finding that they were entitled to qualified immunity.

A police officer on the scene of the motorist's accident requested that he produce documentation of auto liability insurance for his vehicle, and the plaintiff refused to answer the question, based on prior advice from an attorney. The officer first told the motorist he would be arrested for obstruction of justice if he continued to assert his Fifth Amendment privilege. The officer's supervisor, summoned to the scene, repeated this warning, but the motorist still refused to comply.

As the motorist was being taken to the hospital to be treated for his injuries, the officer served him with a "Confirmation of Liability" form, which required that he furnish liability insurance information to the Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles within thirty days, as well as two summonses for operating an uninsured motor vehicle without paying a $500 uninsured motorist fee (an acceptable alternative to insurance under Virginia law), and for obstruction of justice.

The motorist was convicted of obstructing justice but the charge of failing to maintain insurance was dismissed. The obstruction of justice charge was later dismissed on appeal, and the motorist filed his federal civil rights lawsuit.

The appeals court found that the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Chavez v. Martinez, 538 U.S. 760 (2003), barred a federal civil rights claim for violation of the Fifth Amendment regardless of whether or not the Fifth Amendment would exclude admission in court of insurance information produced under compulsion.

In Chavez, the plaintiff was allegedly interrogated in a coercive manner, but was never prosecuted based on that interrogation. A four-Justice plurality of the Court found that "a violation of the constitutional right against self-incrimination occurs only if one has been compelled to be a witness against himself in a criminal case." Two Justices (Souter and Bryer), although not joining this plurality, agreed that the Fifth Amendment focuses on the use in court of a criminal defendant's compelled self-incriminating testimony, and that the enforcement mechanism therefore was the exclusion of such evidence rather that a civil lawsuit for damages.

In the immediate case, the motorist did not claim that there was any action at his trial that violated his Fifth Amendment rights, as he had not furnished any compelled information regarding his insurance status. Given the finding that there was no constitutional violation, the motorist's claim that the city caused a constitutional violation by having a policy allowing officers to question motorists about their liability insurance and issue them citations if they do not answer would also necessarily fail.

The appeals court also rejected the motorist's Fourth Amendment claim, finding that it was permissible for the officers to draw a negative inference from his failure to answer questions about his insurance status, and therefore to issue him the summonses. His silence could be properly considered by the officers as evidence that he neither had insurance nor had paid the uninsured motorist fee, justifying the issuance of one of the summonses. In refusing to answer the officers' questions, the motorist could also be believed to be attempting to prevent the officer from carrying out his duty under Virginia state law, to provide, within 24 hours, a written report, including insurance information of the parties of any accident involving injury. This provided probable cause for the second summons for obstruction of justice.

The individual defendants were therefore entitled to qualified immunity.

Burrell v. Virginia, No. 02-2347, 2005 U.S. App. Lexis 1329 (4th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Federal appeals court rejects claim that police officers violated a man's rights to equal protection by failing to arrest his former boyfriend, a member of the City Council, following an alleged domestic disturbance at their home.

After a physical fight with his former boyfriend, an Illinois man filed a lawsuit against his alleged assailant and three police officers who allegedly refused to arrest him due to his position on the City Council. The lawsuit claimed, among other things, that the officers' refusal to arrest the former boyfriend violated the plaintiff's equal protection rights under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The trial court rejected the officers' claims of qualified immunity, finding that the plaintiff's equal protection rights were "clearly established" at the time of the incident and that there were material questions of fact as to whether the officers actually violated those rights. The trial court reasoned that the equal protection right at issue was to not have police protection withdrawn for purely personal reasons.

A federal appeals court disagreed.

The plaintiff and his former boyfriend, a member of the Peoria, Illinois City Council, moved into a home together after beginning a personal relationship "with sexual overtones." When they began to have difficulties in their relationship, the City Council member allegedly met with the chief of police to discuss those problems and to ask the police chief how he could have the other man removed from the home. The plaintiff heard about this conversation and began making plans to move out.

The plaintiff was subsequently confronted at the house by the City Council member, who allegedly swore at him, slapped him, and punched him in the face. He called "911" and told an operator that he had been assaulted. Two police officers were dispatched to the house, and in the lawsuit, the plaintiff claimed that they laughed and "made faces" when he mentioned his relationship with the City Council member.

The City Council member then called the police chief, according to the plaintiff, who subsequently called the two officers and told them that if there was insufficient evidence of a crime, they should take statements from both men and escort the plaintiff off the property. The plaintiff tried to get criminal charges brought against the City Council member, but was allegedly told by a local prosecutor that this could not be done because it was a "homo thing."

The lawsuit claimed that police protection was improperly withdrawn from him because of animus towards him and favoritism towards the City Council member.

The appeals court stated that it was difficult to find any equal protection violation in the case, since the plaintiff had not shown that he was subjected to unequal treatment. He had "presented no evidence that the police officers treated him differently than other citizens in the context of domestic violence incidents," according to the court.

Lunini [the plaintiff] identifies no similarly situated individual who has been treated differently by Peoria police, and there is no indication that the Peoria Police Department always arrests an alleged assailant when responding to a domestic violence report--indeed we would be surprised and alarmed if this were the case. To the contrary, the district court notes that at least one of the appellants has in the past "responded to domestic violence calls in which he did not make an arrest, even though he observed physical injury, and the injured person stated that someone else had hit him."

The appeals court found that the provisions of a police department general order concerning the procedures for responding to domestic violence reports did not create any explicit duty to arrest the City Council member under the circumstances. It stated that it was "far from clear" that the incident involved anything "other than an ordinary exercise of police discretion" so that it was not obvious that the failure to make the arrest implicated any equal protection rights at all.

The appeals court pointed out that there was no claim that the City Council member posed any continuing danger to the plaintiff when the police arrived at the home, or that there was any threat of renewed assault. Under those circumstances, it would be difficult to say that the failure to make an arrest amounted to a "withdrawal of physical protection in any meaningful sense."

The applicable law on the subject of equal protection violations against a "class of one," as opposed to members of a suspect or semi-suspect classification--such as members of a race or gender--was not "clearly established" at the time of the arrest in 2000, the appeals court further found, so that the officers were entitled to qualified immunity in any event.

The appeals court expressed its belief that under the circumstances, an ordinary police officer could not know that he or she risked violating the plaintiff's civil rights by failing to arrest the City Council member.

Lunini v. Grayeb, No. 04-1822, 2005 U.S. App. Lexis 885 (7th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Officers had probable cause to arrest company vice-president for allegedly overstating the amount of a loss from a theft of cigarettes from the company warehouse, based on evidence known to them prior to the arrest.

After cigarettes were stolen from a beverage company's warehouse, the detective leading the investigation concluded that a company vice-president had "overstated" the amount of the loss from the theft to the company's insurer and to the police. The detective then arrested the vice-president for theft and making a false report to officers. He was later formally charged with these crimes, as well as with insurance fraud.

Months after the arrest, the detective discovered a surveillance camera videotape that showed part of the warehouse's cigarette room during the time when the theft reportedly occurred. He found this while cleaning out his desk during his last day as a detective. The tape had been left on his desk before the arrest in a brown sack, which the detective placed in his desk without opening. After he found it, he watched it and took it to the department's property section, where it was mislabeled by a clerk as a "twenty-two page report," so that it went unnoticed until after the arrestee's acquittal, when the arrestee retrieved all of the evidence relating to his case.

The videotape allegedly cast doubt on the credibility of an individual whose statements the detective relied on during his investigation, and whose testimony was used at the criminal trial. The video showed this individual's daughter, who also worked for the beverage company, handing cigarettes to unknown individuals, and also revealed that the witness arrived at the premises on the day of the theft earlier than she had told the police, and that upon her arrival, she told a co-worker about the theft before entering the warehouse where, according to her subsequent statements to the police, she discovered that the cigarettes were missing. The videotape also allegedly showed that once this witness was in the warehouse, she "rearranged some of the cigarettes in a suspicious manner."

A federal appeals court upheld summary judgment for the defendant detective and another officer in the arrestee's federal civil rights lawsuit, finding that there was probable cause for the plaintiff's arrest.

Given the facts known to the detective at the time of the arrest, a prudent person would have been justified in believing that the arrestee had committed a crime, the court found. The detective's failure to open the bag containing the surveillance videotape until his last day on the job, when he gave it only slight attention by watching it in fast-forward mode, the court stated, "does call his competency into question." But the other evidence available from the officers' interviews with multiple witnesses and examination of documents was sufficient to convince the appeals court that there was probable cause for the arrest.

Such probable cause, the court further asserted, would still have existed even if the defendants had been familiar with the videotape before making the arrest. While the videotape captured the period during which the theft occurred, it actually "sheds no light" on whether the arrestee fraudulently inflated the loss from the theft in order to receive more money from the company's insurer, which was the supposed conduct that actually formed the basis for his arrest.

While the videotape did call the credibility of one witness into question, it did nothing to undermine statements gathered by the officers from other witnesses concerning the arrestee's actions or to eliminate discrepancies between the company's receipts and its inventory that created suspicion as to whether the amount of the loss had been inflated.

The appeals court also found that the arrestee could not assert a constitutional claim on the basis of the officers' failure to locate the videotape, and the withholding of it from the arrestee for possible use in connection with his criminal trial. The arrestee claimed that this denied him his due process right to a fair trial. But this claim failed, the court asserted, because of the lack of any evidence of bad faith or malice on the part of the officers.

Flynn v. Brown, No. 04-1444, 2005 U.S. App. Lexis 933 (8th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Police officers could not be personally liable for the arrest of a man under a New York state harassment statute, for mailing "annoying" written materials on religious and political issues to a candidate for Lieutenant Governor. While the trial court believed that the statute, when applied in this manner, violated the arrestee's First Amendment rights, the officers did not have fair notice, at the time of the arrest, that the courts would "inevitably" declare the statute unconstitutional.

A New York arrestee filed a lawsuit seeking injunctive and declaratory relief and money damages, based on his argument that his First and Fourth Amendment rights were violated when he was arrested for aggravated harassment under a state statute for mailing non-threatening, although "annoying" religious and political materials to a candidate for state Lieutenant Governor and other "people of the Jewish faith." The arrestee claimed that he sent these materials with the intention of alarming the recipients about current world events that have been "prophesied in the Bible."

A federal trial court, while acknowledging that the statute had never before been declared unconstitutional on its face, concluded that a declaration of its unconstitutionality was "inevitable," so that the arresting officers had fair notice that it should not be used to arrest the plaintiff for this activity, since it violated his First Amendment right to free speech. The officers' motions for summary judgment were therefore denied.

A federal appeals court disagreed, finding that the officers did not have such "fair notice" that the courts would "inevitably" declare the statute unconstitutional, so the officers could not be held personally liable for the arrest.

In the absence of something to direct them to the contrary, officers are entitled to rely on a presumptively valid state statute--until and unless it is declared unconstitutional, the court ruled. "The enactment of a law forecloses speculation by enforcement officers concerning [the law's] constitutionality-with the possible exception of a law so grossly and flagrantly unconstitutional that any person of reasonable prudence would be bound to see its flaws."

In this case, far from being "so grossly and flagrantly unconstitutional" that any reasonable person would believe it was unconstitutional, the appeals court noted, several courts had previously specifically declined to find the statute in question unconstitutional. Accordingly, the officers were entitled to rely on the presumed constitutionality of the statute in making the arrest. The trial court was instructed to grant the officers summary judgment on the basis of qualified immunity.

The majority of the three-judge panel did not reach the question of whether the statute was indeed unconstitutional, although the third judge, concurring in the judgment, expressed his strong belief that it was.

Vives v. City of New York, No. 03-9270, 393 F.3d 129 (2nd Cir. 2004).

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Elementary school's detention and questioning of ten-year-old student after her classmates claimed that she had brought a handgun to school, and the subsequent involvement of police officers in continuing to detain and question her, and searching the school grounds for the gun, did not violate the constitutional rights of either the student, or her mother, who was not notified of the detention or questioning until it was over.

Several students at a Virginia elementary school told their teacher that a ten-year-old classmate had brought a gun to school. During the subsequent investigation, school administrators twice held the student in the principal's office for questioning. During the second detention, law enforcement officers also questioned the child. The child's mother was not contacted until the police had left.

The child's mother claimed that the school's failure to notify her of her child's detention and questioning violated her due process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment, and also violated her child's Fourth Amendment right to be free from unlawful seizures.

A federal appeals court affirmed this result. It stated that "school officials must have the leeway to maintain order on school premises and secure a safe environment in which learning can flourish." It expressed the concern that "over-constitutionalizing" school disciplinary procedures could undermine the ability of educators to achieve those goals.

Imposing a rigid duty of parental notification or a per se rule against detentions of a specified duration would eviscerate the ability of administrators to meet the remedial exigencies of the moment. The Constitution does not require such a result.

Both school administrators and the police questioned the child's accusers as well as the child herself, who repeatedly denied bringing a gun to school, and on several occasions asked for her mother. No gun was ultimately found, either in the child's possession or in a nearby area on the school grounds where a fellow student claimed she had seen the handgun discarded.

While students do not "shed their constitutional rights" at the "schoolhouse gate," the appeals court noted, school officials have been allowed "substantial leeway to depart from the prohibitions and procedures that the Constitution provides for society at large."

This leeway, the court reasoned, is especially necessary when school discipline is involved.

With these injunctions in mind, we decline to announce a requirement of parental notification or a ban on detentions of a certain length when school officials are investigating a serious allegation of student misconduct. Such strictures would be particularly inappropriate when, as here, several students corroborate the accusation and an eyewitness shows the investigators where the transgression occurred.

Further, when faced with "imminent danger" to student safety, school officials "may well" find that an immediate inquiry in the absence of a parent is a necessary investigatory step. The judges also were convinced that a federal court was "not the best forum" to address concerns about parental notification, and that Virginia state law indeed requires that a principal notify a parent of any student involved in an incident including the carrying of a firearm onto school property. The parent and child in this case could have pursued their grievances with the school board, and even sought state judicial review if they were not pleased with the result, the appeals court noted.

In the final analysis, the balance of rights and interests to be struck in the disciplinary process is a task best left to local school systems, operating, as they do, within the parameters of state law.

The court also reasoned that, as the student was on school property during the investigation, she was under the "guardianship" of the school administrators. The court concluded that there was no violation of the parent's due process rights.

As for the Fourth Amendment claim, the appeals court had no difficulty in finding that there were reasonable grounds for the detention and questioning based on the allegations of the student's classmates that she had brought a handgun to school.

Nor was it improper to summon the police. Law enforcement officers, the court pointed out, more than school administrators, have a "particular expertise in safely retrieving hidden weapons," so that it was "eminently reasonable" for the school to contact the officers once it became "plausible that a handgun had been secreted in the school's environs."

Detaining the student until it was clear that no gun was located where she could retrieve it made sense to the court, and the court found that the constitutional standards governing searches and seizures of students in such circumstances were very similar to those regulating investigatory stops by police when there is a reasonable suspicion that "criminal activity may be afoot."

When school officials constitutionally seize a student for suspected criminal activity and provide the basis for their suspicion to the police, the court found, any continued detention of the student by the police is "necessarily justified in its incipience," and that is exactly what happened in this case. The detention only continued until the school and officers were satisfied that no handgun was present.

Wofford v. Evans, No. 03-2209, 390 F.3d 318 (4th Cir. 2004).

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Officer acted in an objectively reasonable manner in shooting a 15-year-old burglary suspect who advanced on her with a knife. Suspect's guilty plea to a criminal charge of threatening the officer with the knife precluded her from disputing that fact in her subsequent civil rights lawsuit.

A 15-year-old Colorado arrestee claimed that a police officer used excessive force in the shooting her in the course of the arrest, and also asserted that the police department and chief of police inadequately trained and supervised the officer. A federal appeals court has upheld the trial court's order granting the officer summary judgment on the basis of qualified immunity and dismissing the claims against the other defendants.

The officer encountered the plaintiff and another girl, both of whom were allegedly drunk, at an apartment complex where they were suspected of having stolen a purse. When she attempted to handcuff the plaintiff, she ran into her sister's second story apartment where she went into the kitchen, grabbed a 6 to 10 inch knife, and then ran toward the back bedroom. The officer called for emergency backup and followed the suspect.

The suspect was attempting to leave through a bedroom window, and had successfully cut the window screen with the knife and placed one leg out the window when the officer entered the bedroom and ordered her to stop. The suspect then allegedly turned around and came at the bedroom door with the knife in her hand, while the officer retreated down the hallway. This was repeated once. The officer repeatedly ordered the girl to exit the bedroom and drop the knife.

The girl finally exited the bedroom into the hallway, put the knife up to her chin, and threatened to kill herself. The girl started advancing towards the officer. The officer, with her gun drawn, told the suspect "If you don't stop where you are, I'll have to kill you." The girl allegedly responded by saying, "Okay. Kill me." From about five feet away, the girl turned the knife towards the officer, raised it up and started "hacking it in the air." The officer then shot her once in the abdomen, and the suspect fell to the floor.

The suspect subsequently pled guilty to felony menacing and second-degree burglary, admitting that she had knowingly placed the officer in "fear of imminent serious bodily injury by the use of a knife using threats or physical actions," and she was sentenced to six years imprisonment.

In her subsequent federal civil rights lawsuit, she disputed the facts that led to her conviction by guilty plea, claiming that she had not advanced towards the officer after she exited the bedroom, and that the officer shot her as she stood in place holding the knife to her own throat.

The federal appeals court held that a party who has pled guilty to a crime in a Colorado state criminal proceeding is barred, under the doctrine of collateral estoppel from relitigating the elements of that crime in a subsequent civil proceeding, and that the plaintiff therefore could not claim that she had not threatened the officer or placed her in fear of bodily harm.

Since the use of deadly force is constitutionally permissible if a reasonable officer would have had probable cause to believe that there was a "threat of serious physical harm to themselves or to others," the officer acted in an objectively reasonable manner in using deadly force, the court concluded.

The appeals court also rejected the plaintiff's argument that the officer had recklessly and intentionally created a situation in which deadly force became necessary by "cornering" her in the back bedroom, repeatedly ordering her out of the bedroom, and attempting to open the bedroom door even though she allegedly had no means of escape. The appeals court noted that the plaintiff had tried to escape from the bedroom through the window, and that the officer sent a fellow officer to secure the area outside that window.

The officer's decision to "coax" the plaintiff out of the bedroom instead of simply waiting for backup to arrive, the court reasoned, was "far from reckless," and doing otherwise might have risked the plaintiff escaping while "armed and agitated," posing a danger to the officer waiting outside the building.

The officer's actions were taken, the court found, in response to the attempted escape of a felony suspect, "with deadly weapon in hand, out a window that may or may not have been secured." The officer was therefore properly granted qualified immunity from liability.

Since the officer acted in an objectively reasonable manner, and did not violate the plaintiff's constitutional rights, claims against the city, the police department, and the police chief were also precluded. In order to show that a municipal policy or custom caused a constitutional deprivation, there must be some constitutional violation to begin with. In this case, there was none, so the claims against the other defendants were properly dismissed.

Jiron v. City of Lakewood, No. 02-1421, 392 F.3d 410 (10th Cir. 2004).

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

An arts festival, held under a permit on barricaded city streets, which was free and open to the public, was a traditional public forum for First Amendment purposes. Off-duty police officer in uniform, serving as security for the private group holding the festival, violated a man's rights by threatening him with arrest for walking around there wearing a sign with a religious message and distributing religious leaflets.

An Ohio man was in the habit of attending public events to "proclaim and communicate" his religious beliefs by wearing signs, singing, preaching, distributing leaflets or talking to people. Every July, the Columbus, Ohio Arts Council organizes an arts festival which is held along the riverfront in the downtown area of the city. Certain streets are barricaded during the festival and the street there is open to pedestrians and vendors who set up alongside the road. The festival was conducted under a permit issued by the city for free events open to the public.

On June 8, 2002, the man attended that year's arts festival wearing a sign with a religious message, walking up the barricaded street. When he attempted to walk back down the street, he was approached by an off-duty city police officer who the Arts Council had hired to serve as security. The officer was wearing his uniform and badge, and he identified himself as a officer and informed the man that the event's sponsor did not want him there wearing his sign and distributing literature.

The officer told him to move beyond the barricades and told him that he would be arrested if he did not comply. He complied, because of his fear of arrest. He was subsequently allegedly deterred from attending another festival in the same area because of this incident.

The man sued the city, the police chief, and a city attorney, seeking injunctive relief, declaratory relief, and damages. The City took the position that the area where the man had been distributing leaflets was not a public area where there were traditional First Amendment rights, but rather an area used by a private group for their own purposes. The trial court agreed, and found that the off-duty officer was merely enforcing the rules of the Arts Council, a private group.

On appeal, the appeals court agreed with the plaintiff that such festivals, which are free and open to the public, and held under a non-exclusive block party permit, constituted a traditional public forum, and that the city--not the private entity hosting the festival--deprived him of his constitutionally protected right to freedom of speech under the circumstances.

Despite the permit, the street there remained a traditional public forum, and the plaintiff had the right to be there and express himself, the court found. His religious message was clearly protected speech. Additionally, this was not one of those circumstances in which restriction of speech was justified by circumstances like traffic control or similar requirements. This was also not an instance in which the plaintiff sought "inclusion in the speech of another group." It was unclear to begin with whether the arts council was actually expressing a particular message, and indeed, the festival was most likely an event that had artists expressing various messages of their own.

Additionally, there was no showing that the plaintiff's sign wearing or literature distribution interfered with or would have prevented the "message" of the festival from being conveyed. As the festival was open to the public, it was not a private event.

As for the officer's actions, regardless of whether he was on or off-duty at the time, he presented himself as a police officer, and threatened the use of his arrest powers if his orders were not complied with, and therefore acted under color of state law. Further, the city, in issuing a permit to a private group to use public streets for a festival could not provide the private group with complete discretion to exclude those seeking to exercise their right of free speech. There also was no evidence of any rule having been adopted by the Arts Council limiting expressive activities in the festival area.

The appeals court noted that the city had not offered "an interest, let alone a compelling one," to explain why it prohibited the plaintiff from exercising his First Amendment rights in a traditional public forum.

The right to free speech, the appeals court concluded, "may not be curtailed simply because the speaker's message may be offensive to his audience." On remand, the trial court was instructed to enter judgment for the plaintiff and consider what damages, if any, should be awarded to him.

Parks v. Columbus, No. 03-4096, 2005 U.S. App. Lexis 1219 (6th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

City's ordinance requiring a landlord to institute eviction proceedings against a tenant when the chief of police has a suspicion that the tenant engaged in or permitted illegal drug or gang activity ruled to be an unconstitutional violation of procedural due process rights.

A landlord in the City of Buena Park, California filed a lawsuit challenging a city ordinance which requires the commencement of eviction proceedings against "all occupants" of a rental unit when the chief of police suspects that the tenant has engaged in or permitted illegal drug activity, gang-related crime, or a drug-related nuisance in or near the rented property.

An intermediate California appeals court upheld a trial court judgment striking down the ordinance as unconstitutional as a violation of procedural due process.

The court found that the ordinance exposed landlords to a "substantial risk" of the erroneous deprivation of property rights through compelled eviction litigation, unwarranted fines and penalties, and countersuits by tenants, violating procedural due process.

The court found that the ordinance's procedures were "constitutionally infirm" in three ways. First, in that the notice requiring the landlord to institute the eviction proceedings provided landlords with insufficient information to successfully prosecute such a case. Second, the ten-day period stated within which the landlord is required to begin the eviction proceedings was found to be too short. And finally, the ordinance improperly required the landlord to prevail in the eviction action or else face fines, penalties, a lien on his or her property, or even punishment for a misdemeanor offense.

The plaintiff landlord had rented an apartment to an individual, and after three years of tenancy, city police cited the tenant's roommate for possession of drug paraphernalia. The roommate subsequently participated in a drug treatment diversion program under the terms of which his plea of guilty is not considered a criminal conviction "for any purpose." Following that, the landlord received a letter from the city's police chief giving him ten business days to institute eviction proceedings against the tenant, and to "diligently prosecute" the eviction, as required by the city's ordinance, the "Narcotics and Gang-Related Crime Eviction Program."

The landlord appealed the notice to the city manager within ten days of receiving it, as provided by the notice. The city manager denied the landlord's appeal, and the landlord filed suit in state court challenging the constitutionality of the ordinance.

In upholding the injunction against the enforcement of the ordinance, the appeals court acknowledged both the landlord's important property interests in collecting rent, and the city's interest in combating criminal activity, especially drug and gang related crimes.

But in this case, the court found, the notices required to be sent did not contain enough specific information to aid the landlord in the eviction action, but instead only the alleged offender's identity, apartment number, and the mere dates and times of the alleged criminal activity or arrest.

The court stated that it was not suggesting that due process required that the city's allegation of illegal conduct had to be documented by the observations of a law enforcement officer, but "rather, the documented observations of any witness willing to testify, such as a neighbor or an informant, would supply probable cause for the landlord's unlawful detainer action and give the landlord a chance at success in the action."

The ten-day time period in which to initiate the eviction proceeding was "not nearly enough time" for the landlord to "bolster his evidence" or otherwise investigate the matter and develop his case.

Further, under the ordinance, if the landlord fails to prevail in the eviction action, even if this is the result of "inadequate documentation" provided by the city, the penalties under the ordinance included fines of up to $500, misdemeanor punishment for a fourth violation, and a lien against the property and a civil penalty if court action is required to enforce the ordinance.

The court rejected the city's defense of its procedures, which was based on the fact that the landlord is allowed to appeal to the city manager the police chief's determination that the ordinance applies. "But the ordinance provides no guidance to the city manager regarding the adequacy of the police chief's notice and, in any event, the landlord who does not succeed in a court of law would take little comfort from the city manager's contrary assessment of the merits."

A concurring opinion by one judge on the three judge panel agreed that the ordinance violated procedural due process but he expressed his misgivings that the ordinance might also suffer from "other, more fundamental" constitutional problems, including "its sweeping requirement that all occupants of the premises must be evicted for the sins of one, its disparate treatment of property owners and renters (our record reflects no nuisance abatement efforts against the owners of property for similar crimes), and the Damoclean substantive due process issue which hangs over this statutory scheme."

Cook v. City of Buena Park, No. G031326, 2005 Cal. App. Lexis 105 (Cal. 4th App. Dist. January 28, 2005)

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

The seizure and immediate euthanization of over 200 dogs and cats seized from a woman's trailer home and its attached fenced-in yard did not give rise to a viable claim for deprivation of property without due process of law when the county employees' actions were "random and unauthorized" under state law. This made it impracticable to provide a pre-deprivation hearing, and was not unconstitutional so long as there were available state remedies to compensate the woman for any losses.

A South Carolina woman claimed that the euthanization of more than two hundred dogs and cats seized from her residential property violated her procedural due process rights. A federal trial court granted summary judgment to the defendants in her federal civil rights lawsuit.

Upholding this result, a federal appeals court noted that the question of whether there is a constitutional claim for deprivation of property by government agents is analyzed under the U.S. Supreme Court's decisions in Parratt v. Taylor, 451 U.S. 527 (1981), Hudson v. Palmer, 468 U.S. 517 (1984), and Zinermon v. Burch, 494 U.S. 113 (1990).

In each of those cases, the Supreme Court evaluated the viability of a claim under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983 that state employees, disregarding established state procedures, deprived the plaintiff of property or liberty without a prior hearing in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's due process clause. In Parratt and Hudson, the Court ruled that such a deprivation cannot be challenged under § 1983 if the employees' conduct was "random and unauthorized" -- rendering it impracticable for the State to provide a predeprivation hearing -- so long as the State has provided for an adequate postdeprivation remedy--such as a hearing after the loss of property. In Zinermon, the Court explained that the Parratt/Hudson doctrine is not applicable if the State had accorded its employees broad power and little guidance in effecting the deprivation.

In rejecting the plaintiff's claims for the destruction of her animals, the trial court had found that it was carried out in violations of the procedures spelled out in South Carolina law, and was therefore out of the State's control, and that the postdeprivation remedies available under state law were adequate to compensate her for her losses.

On appeal, the plaintiff argued that her claim should have been deemed saved by the principles set forth in Zinermon, in light of a locally adopted policy which gave discretion to an official to euthanize animals who were thought to be sick or injured.

The Plaintiff was involved in "animal rescue" activities through various volunteer organizations including a group called Carolina Castaways. She adopted dogs and cats from shelters where they otherwise may have been euthanized, and kept them inside and outside her single-wide mobile home and its small fenced backyard. Local residents made a number of complaints regarding the number of animals the woman kept at her home, and their condition.

A local veterinarian complained to a deputy sheriff after the number of dogs appeared to double, and the deputy drove by to investigate. He smelled a "strong" animal odor and heard a large number of barking dogs. He obtained a search warrant from a local magistrate judge calling for a search of the residence and the seizure of any animals that had been mistreated or improperly housed. The deputy was accompanied to the home by the complaining vet, who he knew intended to immediately euthanize at least some of the animals, but he had failed to share that information with the judge.

The deputy had also conferred about the search with the supervisor of the county's animal control. When it turned out that the county's shelter was nearly at full capacity, the vet said that all the animals to be taken from the property were "diseased" and needed to be euthanized anyway. The vet had not, at that point, closely examined the animals, as this was prior to the search.

The dogs and cats were removed from both inside and outside the home and the woman was placed under arrest for ill treatment of the animals, charges which were later dropped. A total of 82 dogs and 129 cats were seized. All but two of the dogs and some of the cats had been euthanized by the following morning. The woman was given permission to take the two surviving dogs and her choice of five of the remaining cats, with those cats not selected killed later that morning.

The vet later conceded that if he had examined the dogs once they arrived at the shelter, as many as fifteen to twenty of them might have been found healthy enough to save. The record in the lawsuit reflected that this was the first and only time that county officials had immediately, "and, one could find, indiscriminately" destroyed animals that had just been seized in connection with the arrest of their custodian for their alleged mistreatment.

It was undisputed that the woman was not provided with notice or an opportunity to be heard before the euthanization of her dogs and cats, and that, taking the evidence in the light most favorable to the plaintiff, there were no "exigent circumstances" requiring the immediate destruction of the animals. The appeals court, however, agreed with the trial judge that the destruction was the result of the county employees' "random and unauthorized acts," so that only post-deprivation remedies to compensate the plaintiff for the loss were required.

A state statute had procedures in place for the care and disposition of animals seized from their owners, which were not followed in this case. The appeals court further found that the immediate case was not equivalent to the situation analyzed by the U.S. Supreme Court in Zinermon, because the defendants in the immediate case were not given authority under South Carolina law to destroy the animals immediately after seizing them.

The plaintiff argued that the deputy and other defendants were given more discretion under a county policy. But the appeals court noted that this local county policy was not part of the record when the trial court considered summary judgment motions, and only authorized the immediate euthanization of animals in exigent circumstances, which were not present here, and further, only applied when animals were brought into the shelter after normal working hours. In this case, the seizure plainly began during normal working hours.

Bogart v. Chapell, No. 03-2092, 2005 U.S. App. Lexis 1650 (4th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

•••• Editor's Case Alert ••••

Update: U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, rehearing case en banc, rules by 10-3 that "intent to harm" is the appropriate legal standard for liability for motorist's death caused by collision with police vehicle going through red light at high speed while responding to a domestic disturbance call. Prior adoption of "deliberate indifference" legal standard by appeals panel overturned. Majority of court also finds that deputies would be entitled to summary judgment, under the circumstances, even under the lesser "deliberate indifference" standard.

As previously reported, a 2-1 majority of a three judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit held that "deliberate indifference," rather than an "intent to harm" was sufficient to impose liability under circumstances where a police vehicle collided with another motorist after allegedly running a red light at high speed while responding to a domestic disturbance call. The panel majority found that the officer's actions, if as described by the injured motorist, could constitute deliberate indifference to the possibility of harm coming to other drivers and their passengers, so that the officer was not entitled to summary judgment on the basis of qualified immunity. Terrell v. Larson, #03-1293 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 11417 (8th Cir.), [PDF], reported in the July 2004 Liability Reporter.

The full appeals court granted a rehearing en banc and by a 10-3 vote overturned the panel's decision as to the applicable legal standard. The court's majority ruled that the "intent to harm" standard set forth by the U.S. Supreme Court in County of Sacramento v. Lewis, 523 U.S. 833 (1998), applies both to an officer's decision to engage in high-speed driving while responding to emergency calls, and to the way in which the police vehicle is then driven in going to the location of the emergency.

In County of Sacramento v. Lewis, the Supreme Court held that, "in a high-speed automobile chase aimed at apprehending a suspected offender . . . . only a purpose to cause harm unrelated to the legitimate object of arrest will satisfy the element of arbitrary conduct shocking to the conscience, necessary for a [substantive] due process violation."

The 8th Circuit subsequently ruled that this legal standard applied to all Sec. 1983 substantive due process claims arising out of the conduct of officers engaged in high-speed auto chases aimed at catching a suspected offender, regardless of whether the chase conditions gave the pursuing officers "time to deliberate." Helseth v. Burch, 258 F.3d 867, 871 (8th Cir. 2001) (en banc), cert. denied, 534 U.S. 1115 (2002). [PDF]

In the immediate case, what was involved was a response to a domestic disturbance call, however, rather than a high-speed pursuit of an offender. The deputy sheriffs drove through a red light with their emergency lights and sirens activated and collided with another motorist's vehicle. The driver of the other vehicle died, and her family claimed that the deputies, in recklessly driving through the red light, violated her substantive due process rights.

The plaintiffs in the case conceded that there was no evidence that the deputies intended to harm the motorist, but argued that the question of whether the deputies were responding to an emergency was a disputed issue of fact which would determine whether deliberate indifference or intent to harm was the applicable standard of fault.

In determining that the required "level of culpability" for liability in this case was "intent to harm" rather than "deliberate indifference" to the risk of harm, the appeals court's majority rejected the conclusion that Lewis was limited to high-speed police driving aimed at apprehending a pursued offender.

Police officers deciding whether to respond to an emergency domestic disturbance call must make a quick decision how best to protect the public and maintain lawful order. Those responding must arrive at the scene quickly to quell violence, protect children, and assist anyone who is injured, so responding from afar will invariably require the same type of high-speed driving as the chase of a fleeing suspect. Domestic disturbances are "notoriously volatile and unpredictable," so the number of police officers needed to defuse the situation is rarely known in advance. Like the officer who made a quick decision to give chase in Lewis, police officers responding to this type of emergency call do not have "the luxury . . . of having time to make unhurried judgments, upon the chance for repeated reflection, largely uncomplicated by the pulls of competing obligations."

Applying a "deliberate indifference" legal standard in this context, rather than the "intent to harm" standard, the court believed would threaten to "deter police officers" from deciding to respond to emergency calls, and thereby increase the risk of harm to persons caught up in these crises.

The majority of the full court also rejected the panel's "objective test" to resolve whether the deputies were responding to an emergency. In doing so, the panel had found that the deliberate indifference culpability standard--rather than the intent to harm standard--would apply if a jury finds that the deputies were not responding to a "true emergency." The full court found that this was erroneous, since a substantive due process claim, like the one asserted by the plaintiffs, "turns on" the government official's evil intent--so the issue was whether the deputies "subjectively believed that they were responding to an emergency, not whether it actually was one.

In this case, the deputies heard an initial dispatch that a young mother had locked herself in a bedroom and was threatening to harm her three-year-old child. From an officer's perspective in deciding whether to respond, the court stated, the dispatch "without question" described an emergency--that is, "a situation needing the presence of law enforcement officers as rapidly as they could arrive, even if that entailed the risks inherent in high-speed driving."

The majority also found, in the alternative, that the deputies were entitled to summary judgment even under the deliberate indifference standard of fault adopted by the majority of the three-judge panel and the trial court.

To prevail on their substantive due process claim, plaintiffs must prove, not only that the deputies' behavior reflected deliberate indifference, but also that it was "so egregious, so outrageous, that it may fairly be said to shock the contemporary conscience." Not all deliberately indifferent conduct is conscience shocking in the constitutional sense of the term. Because the conscience-shocking standard is intended to limit substantive due process liability, it is an issue of law for the judge, not a question of fact for the jury.

The appeals court's majority found that the trial judge and panel majority erroneously failed to consider whether the deputies' conduct was "conscience shocking." It found that the decision to respond to the report of the domestic violence by high-speed driving, while always involving "some risk to highway safety," did not reflect the "criminal recklessness" that is required for substantive due process liability under the deliberate indifference standard.

Traffic accidents of this nature are tragic but do not shock the modern-day conscience.

The fact that the deputy driving the vehicle violated departmental regulations in going through the intersection at high speed could raise an issue of possible liability under state law, "but it is not of substantive due process significance." The appeals court therefore reversed the trial court's order, remanding the case with instructions to dismiss the plaintiffs' federal civil rights substantive due process claims.

A strong dissent by three judges on the court argued that:

Today's decision has the effect of giving police officers unqualified immunity when they demonstrate deliberate indifference to the safety of the general public. A police officer may now kill innocent bystanders through criminally reckless driving that blatantly violates state law, police department regulations, accepted professional standards of police conduct, and the community's traditional ideas of fair play and decency so long as the officer subjectively, though unreasonably, believed an emergency existed. The majority's holding extends Lewis's high-speed pursuit rule from its intended purpose of protecting officers forced to make split-second decisions in the field to a per se rule that now shields officers even after they have had an actual opportunity to deliberate at the police station. Believing that 42 U.S.C. § 1983 gives citizens a remedy for egregious abuses of executive power that deprive citizens of their constitutional right to life, we dissent.

Terrell v. Larson, No. 03-1293 2005 U.S. App. Lexis 1815 (8th Cir.)

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Police officers who searched home of suspects pursuant to search warrant after purchasing VHS videotapes and Nintendo games suspected to be stolen from them in an on-line auction did not violate the Fourth Amendment. Seizure of DVDs, non-Nintendo videogames, and other related materials not specified in the warrant was proper under the plain view doctrine.

Illinois State Police officers were contacted by the vice president of a company that owned several video movie rental stores, and who suspected that one of his employees was stealing merchandise from one of the stores. The employee was a manager who had unregulated access to the store's VHS videotape and video game inventory. He claimed that the manager and her roommate were selling hundreds of videotapes and video game cartridges via the online auction site eBay under the username "TJ198."

The officers soon logged on to eBay and placed bids on a package of 100 videotapes offered for sale there under that username, and won the auction, sending a cashiers check to one of the suspects at a post office box. The tapes subsequently arrived in two boxes, and upon examination many appeared to have labels, tags, bar codes or other stickers identical to those used by the video rental store, with it appearing that stickers of like shape and placement had been peeled off several other tapes.

Based on these facts, one of the officers applied for a warrant to search the home where both suspects lived, reciting these facts and that the suspects had not purchased any movies from the video rental company's corporate parent or its suppliers. The affidavit asserted that the suspects would need "unlimited, confidential access to a computer to manage the suspected high volume of transactions and to stay in constant communication with online bidders," and that this type of access would be available only at the suspects' house.

The warrant issued authorized a search of the suspects' home, and the seizure of video tapes, Nintendo video games, written records of sales, a computer and computer documents, bank records, and email or financial records relating to eBay auctions. Upon executing the warrant, officers discovered boxes with hundreds of videotapes and Nintendo video games, as well as CDs, DVDs, and non-Nintendo games and equipment, some of which were commingled in the boxes with the VHS tapes and Nintendo games. They seized all of these "media items," and a wide range of documents.

Both residents of the home were subsequently arrested. During questioning of one of them, she allegedly signed a written consent form authorizing a search of a storage unit she had rented in a nearby town. The next day, the officers searched that storage unit, seizing all its contents, including 135 boxes of videotapes, Nintendo games, other games, CDs, and a popcorn machine. The residents were charged with felony theft, but these charges were later dropped after they both passed polygraph tests supporting their contention that they had obtained the tapes lawfully and had stolen nothing. The property was later all returned to them. They had purchased the materials, evidently, from store closing sales and from low-cost retailers.

The residents filed a federal civil rights lawsuit claiming that the officers' actions violated their Fourth Amendment rights. The trial court granted summary judgment in favor of the officers on the Fourth Amendment claims, finding that there had been no Fourth Amendment violations, and that, in the alternative, the defendants were protected by qualified immunity. The court declined to exercise jurisdiction over state law claims.

A federal appeals court upheld this result. It rejected the arguments that the search warrant was not supported by probable cause, that the warrant lacked particularity about what was to be searched for and seized, that the officers exceeded the scope of the search warrant, and that the search of the storage locker was without consent.

The plaintiffs claimed that the warrant was not supported by probable cause because the affidavit did not allege that anything had been stolen. Since it is not unlawful per se to possess or sell videotapes or games, the failure to allege that a crime occurred, they argued, was a "missing link" that fatally undermined the warrant. The appeals court noted, however, that the affidavit sought evidence "of the offense of theft" and stated that the company had advised the officer that the store manager had no legal right to any VHS movies or Nintendo games from the store. Affidavits for search warrants, the appeals court stated, are tested and interpreted by magistrates and courts "in a common sense and realistic fashion," and this was sufficient to allege a crime had occurred.

The warrant was based on information from a known, credible witness whose allegations had been corroborated by the officers through the purchase of merchandise.

The appeals court rejected the argument that the warrant was not particular enough since it did not catalogue the individual movie and game titles allegedly stolen from the video store, and therefore would not enable an officer reading it to distinguish between items subject to the warrant and property lawfully possessed by the residents. While the Fourth Amendment requires that the search warrant describe the objects of the search with "reasonable specificity," it "need not be elaborately detailed," and in a case like this, it was sufficient to list the type of items to be seized. The officers had reason to believe that the suspects had stolen "hundreds" of videotapes and games, so that it would have been "impractical" to list all their titles.

The appeals court also found that the seizure of DVDS, CDs, blank videotapes, and non-Nintendo brand video games, in addition to VHS tapes and Nintendo games, while "broad," was constitutionally permissible. Officers executing a search warrant may seize items named in the warrant, as well as evidence that, while not described in the warrant, is subject to seizure because it is in "plain view."

Some of the CDs, DVDs and non-Nintendo brand games were found in the same boxes as the items specified in the warrant, and others were found nearby. In light of the volume of the suspected theft, the location of the items, and their similarity to the items named in the warrant, the officers were justified in seizing them based on a reasonable belief that they were also evidence of theft.

The appeals court also found that police, while executing a valid search warrant for a suspect's home can arrest a resident found there if the officers then have probable cause to believe that they have committed a crime, so the arrest of the plaintiffs, when found home during the execution of the search warrants was valid, and the absence of an arrest warrant did not alter this.

The appeals court also found that the trial court properly found consent to search the storage locker, and properly refused to consider an affidavit by the plaintiff who had signed the consent form which was submitted after the close of discovery, since it did not contain any newly discovered evidence, but instead purported to be based on facts she knew from the start of the litigation. The signed consent form, the court found, was "highly probative evidence" that she consented to the storage locker search, and her initial affidavit, the one that was properly in evidence, even if true, only established that a particular officer did not ask for her consent. The record made it clear, however, that any one of a number of officers present could have asked her to sign the consent form.

Since the officers did not violate the plaintiffs' Fourth Amendment rights, they were properly granted summary judgment, the appeals court concluded.

Russell v. Harms, No. 04-2065 2005 U.S. App. Lexis 1636 (7th Cir. February 02, 2005)

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

EPA inspectors who, exceeding the scope of consent given, took wastewater samples from manhole located on privately owned road near manufacturing mill did not violate the rights of the business. There was no reasonable expectation of privacy in such wastewater when it was flowing towards the public sewer system in a manner making it similar to abandoned trash put out for collection.

The owners of a mill in Massachusetts, Riverdale Mills Corporation, and its controlling stockholder, sued two inspectors for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), claiming violations of their right to be free from unreasonable searches of their business. They claimed that the agents' sampling, without consent or a search warrant, of wastewater from underneath a manhole located on the mills' land was a Fourth Amendment violation. The lawsuit was filed under Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Fed. Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388 (1971), allowing direct claims for purported constitutional violations against persons exercising authority under federal law.

A federal appeals court has overturned the trial court's denial of qualified immunity to the defendant inspectors.

The appeals court found that the plaintiffs had no reasonable expectation of privacy in the wastewater under the circumstances of the sampling, and therefore no Fourth Amendment rights were violated. The appeals court further ruled that, even if this were incorrect, the agents would still be entitled to qualified immunity because the existence of a reasonable expectation of privacy was not clearly established at the time of the agents' actions.

The mill manufactures plastic-coated steel wire products. During manufacture of the product, a water-based cleaning process generates both acidic and alkaline wastewater, and the company has a state permit allowing it to put the wastewater into the public sewer system so long as proper treatment, neutralizing the acidic or alkaline qualities of the water, has been applied before it reaches the public sewer.

The manhole cover from which the EPA agents took the samples is located on a paved street that runs alongside the mill building. The agents stated that it appeared to be on a public street, while the business claimed that it privately owns this street which runs from a public road across its property along the side of the mill. The appeals court assumed, for purposes of the appeal, that the road was privately owned.

The wastewater flows from this first manhole to another manhole 300 feet away which is indisputably publicly owned and part of the public sewer system, and from there eventually flows to the town's treatment plant before being released into a nearby river. Prior to the EPA agents' sampling, they received an anonymous letter from a tipster claiming to be an employee of the mill stating that the plant's pretreatment system was not being run properly, and that the mill therefore might be discharging wastewater with improper pH levels and other problems.

The EPA agents came to the mill without a search warrant or any claim of exigent circumstances, and met with high-level employees of the company, asking for consent to an inspection of the wastewater treatment facility, including tests of the wastewater. The company's controlling stockholder gave them consent on the "express condition" that he or other specified mill employees accompany them at all times.

A first sampling from the manhole was performed in compliance with this condition. One of the inspectors subsequently claimed that he had made it clear to the controlling stockholder that they would be taking additional samples from the manhole throughout the day, and that the stockholder said this was "Okay." The stockholder disputed this, claiming that he was never told that periodic sampling would be conducted throughout the day.

The agents took two additional samples later in the day, after an elapse of several hours, and allegedly did that without the mill employees presented, so that it was outside of the scope of the consent given. The sampling occurred, however, in the street in front of the plant and in "full view" of mill employees. Before leaving, the inspectors also took samples from the second manhole, which was indisputably on public property.

Based on the data from these samples, the EPA obtained first an administrative search warrant to search the mill, and second a criminal search warrant to conduct a search on a subsequent date. These later searches were not an issue in the appeal in front of the court. In the criminal proceedings against the mill and its controlling stockholder for alleged violations of a federal environmental statute, the evidence from the two later samplings from the manhole were suppressed on the basis of exceeding the scope of consent given. The indictment was later dismissed.

In the federal civil rights case, the appeals court found that the company did not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in "industrial wastewater that is on a private street and underneath a 171-pound manhole cover but 300 feet away from and flowing irrevocably into the public sewer system." The court declined to adopt a per se rule that there is never any reasonable expectation of privacy in wastewater, based on an analogy to abandoned trash.

The court pointed out that the case law does not establish that trash can never be protected for Fourth Amendment purposes, but rather that trash left in bags on or near the curb for collection by a third party is unprotected. While it was of some help to the plaintiffs' case that the manhole was purportedly on private property, the wastewater found there was not stationary wastewater in a holding lagoon shielded from public access, but rather was in an area of the mill's property that was most akin to an "open field" rather than to a more heavily protected area like the "curtilage" or interior of a home or business.

Ultimately, the appeals court found the controlling factor to be that the wastewater from the first manhole was "irretrievably flowing" into the public sewer only 300 feet away, and would inevitably reach the second manhole, where the public sewer begins, and from which any member of the public could take a sample. Therefore, the wastewater in the first manhole was there in circumstances similar to trash left out on the curb for pick-up by the trash collector, which enjoys no reasonable expectation of privacy.

Even if the contrary result were reached, the appeals court stated, the EPA inspectors would still be entitled to qualified immunity under the circumstances, since there was no clearly established expectation of privacy in wastewater flowing towards the public sewer.

Riverdale Mills Corp. v. Pimpare, No. 04-1626, 392 F.3d 55 (1st Cir. 2004).

» Click here to read the text of the court decision on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

Report non-working links here

Administrative Liability: Training

Police officer's testimony that he had not been trained concerning the use of force was not sufficient to hold the city and police chief liable for other officers' alleged excessive use of force resulting in a man's death. There was no showing that the alleged failure to train the testifying officer was causally connected in any way with the actions of the officers who allegedly used force against the decedent, and no showing of a widespread pattern of similar incidents of alleged misbehavior. Dabney v. City of Mexia, No. 04-50194, 113 Fed. Appx. 599 (5th Cir. 2004). [PDF]

Assault and Battery: Handcuffs

Officers acted reasonably in handcuffing and detaining a minor girl even if they were aware of her mental disability of Down's Syndrome, when she had failed to comply with their instructions and had produced a gun from her pocket in the course of their investigation of someone knocking on doors in the neighborhood while possibly holding a gun. Further, she was only detained for approximately four and one-half minutes and handcuffed for one and one-half minutes. Tenorio v. City of Hobbs, No. 04-2103, 113 Fed. Appx. 879 (10th Cir. 2004).

Assault and Battery: Physical

Police officer was not entitled to qualified immunity on arrestee's claim that he struck him in the eye while he was surrendering by laying on the ground after ending a chase. The officer's alleged conduct of striking an unarmed suspect about the face after he voluntarily surrendered, if true, was objectively unreasonable. Dubay v. Craze, No. 03-71553, 327 F. Supp. 2d 779 (E.D. Mich. 2004).

Defenses: Collateral Estoppel

A determination by a state traffic tribunal that there had been probable cause under Rhode Island law to stop a vehicle barred relitigation of the issue in the motorist's subsequent federal civil rights lawsuit claiming that the stop was unlawful. Wiggins v. Rhode Island, #02-1418, 326 F. Supp. 2d 297 (D.R.I. 2004).

Defenses: Sovereign Immunity

Passenger in parked police vehicle could not recover damages against city for injuries suffered when the car was struck in the rear by another parked police vehicle which was itself struck in the rear by a truck. Under Texas state law, the city did not waive sovereign immunity when the cause of the injuries was not attributable to the car in which the passenger was sitting, but rather to the negligence of a third party, the truck driver. City of Kemah v. Vela, No. 14-03-01091-CV, 149 S.W.3d 199 (Tex. App. -- Houston 14th Dist. 2004).

Defenses: Qualified Immunity

As of December of 1999, it was clearly established that a police officer could not reasonably believe that it was constitutional to "take down" or physically assault an arrestee who was not actively resisting arrest, attempting to escape, or posing a threat to others, and that other officers present had a duty to intervene to prevent the use of excessive force by a fellow officer. Defendant officers were therefore not entitled to qualified immunity from arrestee's excessive force claims. Hays v. Ellis, #CIV.A.01-K-2316, 331 F. Supp. 2d 1303 (D. Colo. 2004).

Dogs

Police officer who shot and killed a dog which had chased and pinned down a man in his back yard was entitled to immunity from liability under a Louisiana statute providing that an officer may kill any dangerous or vicious animal and shall not be liable for damages as a result of such killing. Hebert v. Broussard, No. 04-485, 886 So.2d 666 (La. App. 3rd Cir. 2004). [PDF]

False Arrest/Imprisonment: No Warrant

Police officer had probable cause to arrest the driver of a pickup truck struck from behind by a tractor trailer. The physical evidence was consistent with the version of the incident given by the driver of the tractor trailer, who asserted that the pickup truck driver pulled in front of him, taunted him, and applied his brakes. Even the arrestee, while denying the taunting, admitted having applied his brakes. Christman v. Kick, No. CIV.A.3:02 CV 1405, 342 F. Supp. 2d 82 (D. Conn. 2004).

Criminal conviction of two arrestees on the charges which they were arrested on was a complete defense to their civil rights false arrest lawsuit, as it conclusively showed that there was probable cause for their arrests. Brown v. Willey, No. 04-1371, 391 F.3d 968 (8th Cir. 2004). [PDF]

Officers' receipt of a report of a drug transaction, their observation of the passing of a packet of what they believed was marijuana from the arrestee to another person, and the recovery of a packet of marijuana was sufficient, taken together, to show probable cause for the arrest. McDade v. Stacker, No. 03-2681, 106 Fed. Appx. 471 (7th Cir. 2004).

Probable cause existed to arrest police officer for physically abusing a 12-year-old minor when the juvenile arrived at a police station in the sole custody of the officer, was bleeding from his nose and mouth, stated that the officer hit him when he had "gotten smart," and the officer failed to offer any explanation to investigators as to how the injuries occurred. Anderer v. Jones, #02-3669, 385 F.3d 1043 (7th Cir. 2004).[PDF]

Student arrested by a state university police officer after another officer told him that the student had assaulted him failed to state a claim for violation of his equal protection rights, since he did not show that he was treated any differently from other similarly situated persons. Cook v. James, No. 03-2391, 100 Fed. Appx. 178 (4th Cir. 2004). [PDF]

False Arrest/Imprisonment: Warrant

Police officer who obtained arrest warrant had sufficient evidence to have probable cause that suspect had been deceiving elderly man for years, having him establish a joint banking account with her from which she later took a substantial sum of money. Officer's affidavit also established probable cause to believe that the arrestee had taken other property. Kane v. Lewis and Clark County, Montana, No. 03-35172, 111 Fed. Appx. 870 (9th Cir. 2004).

Officers had probable cause to arrest man under facially valid arrest warrant that had his name, photo, and social security number, despite the fact that it had an incorrect address for him, and the fact that he subsequently turned out not to be the person who actually committed the drug trafficking offense. Officers could reasonably have believed that the arrestee merely changed his address and were entitled to qualified immunity on his claim for false arrest. Johnson v. Watson, No. 03-4756, 113 Fed. Appx. 482 (3rd Cir. 2004). [PDF]

Firearms Related: Intentional Use

Police officer acted reasonably in shooting and killing a motorist following a traffic stop because the motorist picked up a gun after it fell to the sidewalk and after the officers ordered him not to pick up the gun. Bloxson v. Borough of Wilkinsburg, No. 04-1108, 110 Fed. Appx. 279 (3rd Cir. 2004). [PDF]

Burglar who was shot by police officer when he reached to grab the top of a cabinet in which he was hiding in order to pull himself out established, for purposes of a qualified immunity analysis, that the officer used excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment if the facts were as he alleged, since he then would have posed no threat to the officer, so that the use of deadly force was not objectively reasonable. Sample v. Bailey, No. 5:04CV344, 337 F. Supp. 2d 1012 (N.D. Ohio 2004).

First Amendment

Police officers' decision to prohibit abortion protesters from carrying signs showing aborted fetuses in Halloween parade, and subsequent confiscation of those signs was an impermissible violation of the protesters rights of free speech and assembly and the officers' actions were not "narrowly tailored" to the public safety concerns, when spectators' hostile reactions were only heckling and non-violent threats. Grove v. City of York, Pennsylvania, No. CIV. 1:CV-03-198, 342 F. Supp. 2d 291 (M.D. Pa. 2004).